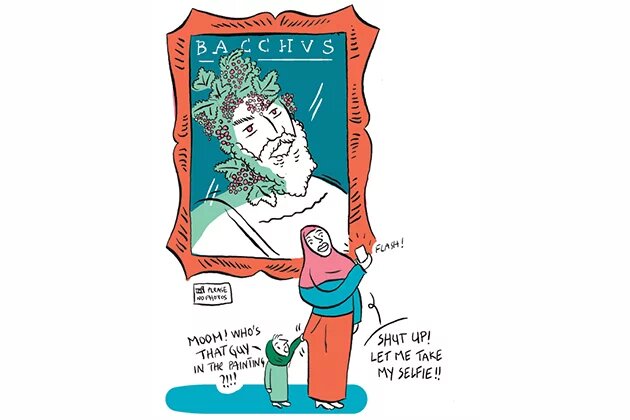

Is Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, alive among us through his elixir, between the leaves of his sacred plants or in the vines, planted for his delight?

Is Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, alive among us through his elixir, between the leaves of his sacred plants or in the vines, planted for his delight?

This story of wine begins on the shores of North Africa, many centuries ago. In Tunisia, the art of growing vines and winemaking dates back to earliest antiquity, and viticulture to the ninth century BC, during the Carthaginian era. Carthage was both the breadbasket and the wine cellar of Rome. Today Tunisia’s vineyards extend over a surface area of 17,500 hectares and are principally located in the northeast of the country. Annual production amounts to 400,000 hectolitres, of which 220,000 are sold on the domestic market, mainly to cater for the five million tourists Tunisia welcomes each year.

Tunisian viticulture can be traced back to the centuries when, through trial and error or simple experimentation, humans discovered spiritual and alcoholic beverages; which in antiquity were spread between cultures around the ‘middle sea.’ Travellers along the southern shores of the Mediterranean basin, the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Carthaginians, introduced wine making with its tradition of technically rigorous practices and understanding. The famed Tunisian agronomist Mago, who lived in Phoenician Carthage, initiated the study and observation of agriculture, devising a set of rules and identifying factors affecting production. His works are still the bible of viticultural agronomy.

Tunisia, the wine cellar of antiquity, was an Eden of agricultural production for luxurious, quasi-sacred produce consumed during the great rituals in Rome; Carthaginian wine was drunk in honour of emperors, temples and soldiers. Life in Carthaginian Tunisia revolved around producing and exporting; clay potters made wine jars, wine presses were installed in large vineyards, and festivals crowned the harvest during the pressing of grapes and the nights when people would dance with Bacchus, celebrating the art of wine and conviviality.

During the Roman era, Tunisia was the breadbasket of the emperors, and wine production became more sophisticated. Tunisia’s favourable climate and generous sunshine led it to exert a monopoly over production. Roman Tunisia introduced a set of criteria for the labelling of wine and wines made by African Romans were drunk at the Vatican during meetings of its conclave and to celebrate mass.

The Roman conquest of North Africa and the wealth of its soldiers led to the planting of vineyards that were larger and more varied than those from antiquity. The sheer density of vineyards enabled this ‘elixir of life’ and intoxication to flow freely throughout the ancient world as the techniques of wine production improved from generation to generation, and from one culture to another.

Then the Byzantines reached Africa, bringing with them their ancient Greek traditions of decorating mosaics, frescoes and statuettes with vine leaves, baskets, bunches of grapes and satyrs. This decorative language drew on the depictions of ancient aesthetic iconography of gods carrying bunches of grapes, nymphs hiding behind vine leaves, and muses mixing their wine with the waters of wisdom. In this era, wine was a social and cultural practice where drinking vacillated between inebriation and the sanctity of wisdom. Poets wrote odes to it, theatre plays alluded to it, philosophers discussed it, and time passed.

The Arabs illuminated the world with the torch of a new religion, and reached the shores of North Africa, Ifriqiyya, in the seventh century with its sea of vineyards that shone green like an emerald, richly verdant, but drained by wars. Islam began to influence daily life; vineyards were no longer the good investments they had once been, and the production of wine was no longer an accepted practice on either religious or sociocultural grounds.

The vineyards’ star began to fade as they became increasingly rare. Some practices did survive, such as wine and wine liquor production on the island of Kerkena, and in a few other corners across Ifriqiyya. Wine was an important character in Arabic poetry. Khamr (الخمر) was the ally of artists, poets, lovers of the Caliphs, and of princes at their soirées. In poetry, Bacchus, a well-known figure at the time, assumed the guise of an Arab warrior from the Orient and sung of his knightly escapades, warrior’s courage and amorous nights. Through his special relationship with the fruits of the vine, Bacchus became synonymous with the wine that ran in the rivers of paradise, conjuring a riverscape through which it flowed. This poetry developed and shared a taste for a culture of wine that was both anchored in the lands of the tizurin (“vines” in the Berber language) and also found in a miraculous grapevine which covered the heavens of Berber mythology, a sky of gracious and fragile leaves that traced shadows of songs and stories. The poet-soldier disembarked in these places, and sang of the blood and gold-coloured waters. These poets, as they swapped shores, demonstrated a new taste for poetry that told of the noble and courageous, the knight and poet in all their manifestations. In literature from the Abbasid era, they would charm through their harmonious and melodic descriptions of wine, it was a source of fantasies, intoxication of the senses, and pleasure, a space where man could forget his troubles and embrace words.

Wine then took on a great significance in sung poetry, of which traces can be found in the music of al-Andalus: “I deprived myself of sleep, o mistress of departures…I revealed our story to my cup …I spoke only to my wine cup…my living is without nourishment…” "حرمت بك نعاسي يا مولات الريام ... وبحت بك لكاسي ... عيشي بلا طعام ..." Poets made declarations of love with their words, pairing sensual nights with wine-fuelled ones. Wine continued to spin its cultural web between Roman palaces and Arab gardens, lands where man lived piously by day, but by night his experience was a spiritual one in which wine lit up sombre, lugubrious evenings. Whilst wine production declined because of the new traditions and moral codes, it could still be found in palaces and large cities, among ethnic minorities, and in the hinterland during festivities, and marriage ceremonies. The lyrics of songs also continued to talk of intoxication through love and wine not only in classical Arabic, but also in the local dialects.

The spirit of Bacchus fought against the new moral code and persisted, like a tree whose roots sing of the past and whose branches, with Eros’ red ink, write the future. During this period, however, wine production made no technical advancements and continued only in a limited way among a few foreign Christian families from Malta and southern Italy, and among the Jewish population. These ethnic groups protected Tunisian wine heritage until the arrival of the White Fathers at the end of the nineteenth century, who along with the Italians who arrived after the treaty agreed with the Bey of Tunis in September 1868, developed and revitalised the Cap Bon region’s vineyards and viniculture. The first vineyard of the modern era in Tunisia was planted at the seat of the Archbishop in Tunis in 1879. Wine began to rival in popularity a fig eau-de-vie, known as Boukha (البوخة), which was a popular traditional liquor in Tunisia’s Jewish community. Wine would not find its place in the codes of local gastronomy, whether popular or refined, but as always it remained linked to nights of pleasure and mysticism.

In 1881 with the establishment of the French protectorate, winegrowers sprung up in great number. Different varieties of wine were produced, and Tunisia once again re-established its wine chart, from red to white wines, via rosé, from the dry to fruity via the sweet. Tunisian wines drew their flavour from the country’s rich soil and harsh sunlight. In the mid-1960s, when the Italian Tunisians left independent Tunisia, wine production underwent another dark period when the presses and vineyards were abandoned. The troubled economic period that infected the country steered wine from an ‘elixir of life’ to a neglected industry until 1999, when the Tunisian Wine Office opened up production to the private sector and offered the opportunity to French, German and Italian specialists and investors to draw up new strategies, benefiting from their rich expertise to revive Bacchus once again.

Wine is the reflection of a civilisation, an art of living and a culture. To appreciate it, one must know its origins: where it comes from, the variety of grape, how it was vinified and by whom. But to discover its soul, one must dive into the history and customs of the country where it was produced. Better still, one should visit the vineyards to take in the landscapes, smell the scent of the earth, and meet those who work to produce it. One must also take an interest in the local gastronomy and the matching of wines to certain dishes. In this way, Tunisian wine would no longer be simply the beverage of couscous restaurants. It would become an independent part of Mediterranean culture that could accompany all types of cuisine. For you readers, it would become one of the world’s must-have wines, one to lay down in your cellar.

And on those occasions when you feel like escaping, just as those moments when one lingers in front of an artwork, you might just sip it among friends, family, or even for an important occasion. Is drinking wine today still a toast to the gods or simply a means to escape reality?